For instance, specific references to disability are neither to be found in the eight Millenium Development Goals defined by the UN, nor in the 18 targets set out to achieve them, nor in the 48 indicators for monitoring their progress (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millennium_Development_Goals). Consequently, international organizations, UN bodies and states often ignore disability when framing their policy agendas, indicator assessments and funding (http://www.disabilitykar.net/learningpublication/developmentgoals.html). It is hard to imagine how international agencies can be serious about achieving the MDGs, if they have no plan nor special resources for the education and other basic needs of the disabled, a tenth of the world population (Social Jurist vs. Union of India and others C.W. 1342/2003 (Delhi High Court)).

While the relationship of any media to censorship is interesting, that of the

Internet is especially so. John Gilmore, who played a key role in the

development of the Internet, made a very widely quoted remark, "The Net

interprets censorship as damage and routes around it," which he explains

thus: "In its original form, it meant that the Usenet software (which moves

messages around in discussion newsgroups) was resistant to censorship

because, if a node drops certain messages because it doesn't like their

subject, the messages find their way past that node anyway by some other

route. This is also a reference to the packet-routing protocols that the

Internet uses to direct packets around any broken wires or fiber connections

or routers... The meaning of the phrase has grown through the years. Internet

users have proven it time after time, by personally and publicly replicating

information that is threatened with destruction or censorship. If you now

consider the Net to be not only the wires and machines, but the people and

their social structures who use the machines, it is more true than

ever."1

Recent events in Burma and Iran highlight this very well. As long as the

Internet was connected to Burma during the last major period of protests,

plenty of information came through, about the brutality there. When the

Burmese government literally pulled the plug on the Internet, it was able to

crack down on the protesters with much greater impunity. Iran, after the

recent elections, was able to control information flow through all other

media, except the Internet. Apparently, even the US State Department had to

request twitter to postpone scheduled maintenance on the site, because it was

such a vital source of information to them. Political reporting may have

undergone a fundamental transformation: one might say that not just

conventional censorship, but even the self-censorship that media agencies and

broadcasters exercise is being increasingly bypassed by the Internet.

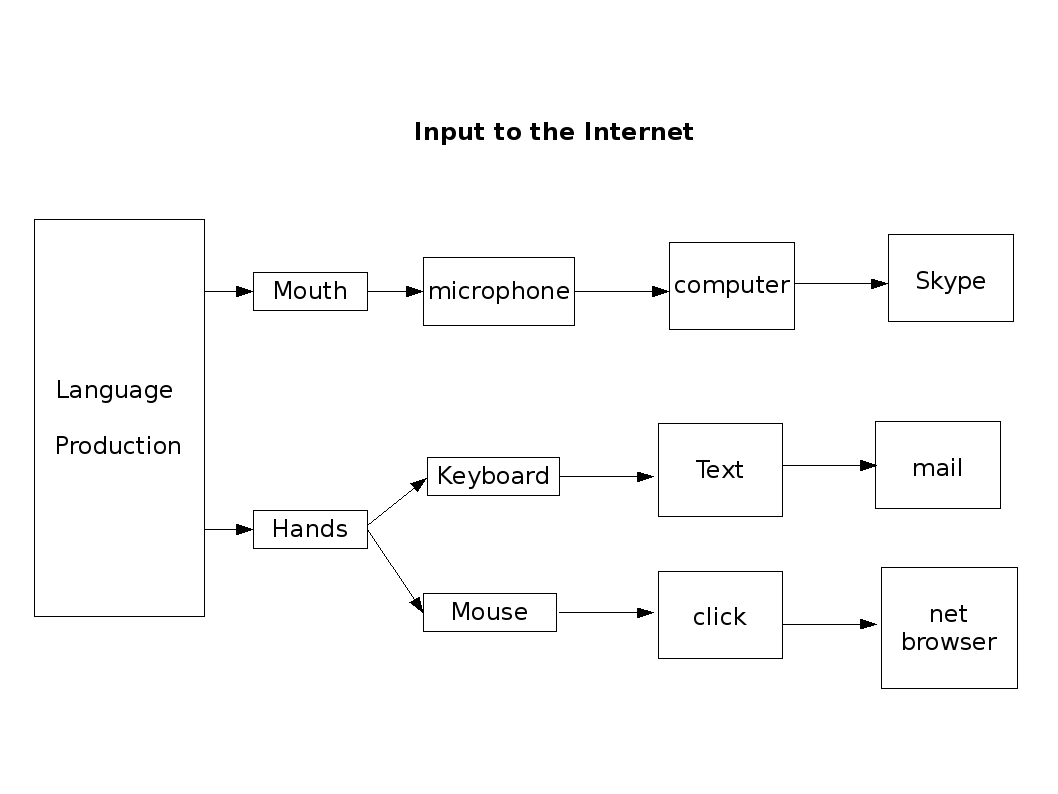

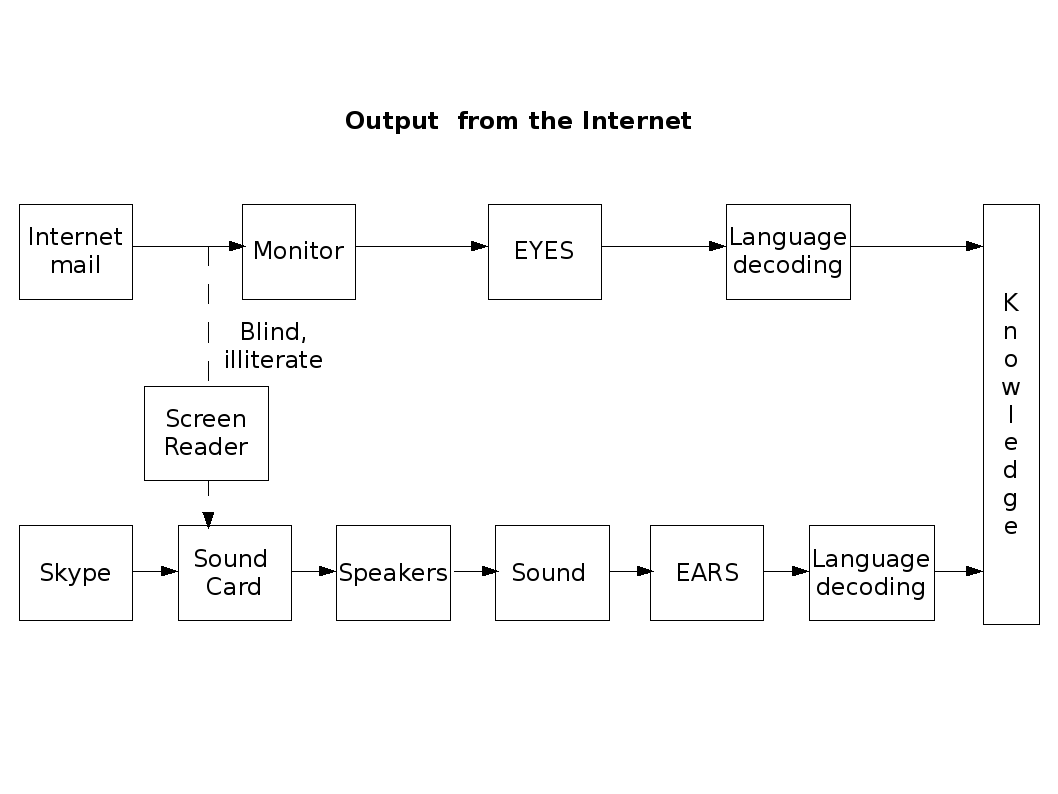

This diagram is also helpful in identifying where the blockages might

arise. To start with, you may not know the language or lack the vocabulary, a

blockage that could be addressed by education.

Then, you may not possess the strength and dexterity in your hands to operate

a keyboard or mouse, or you may not be able to speak. Here, special input

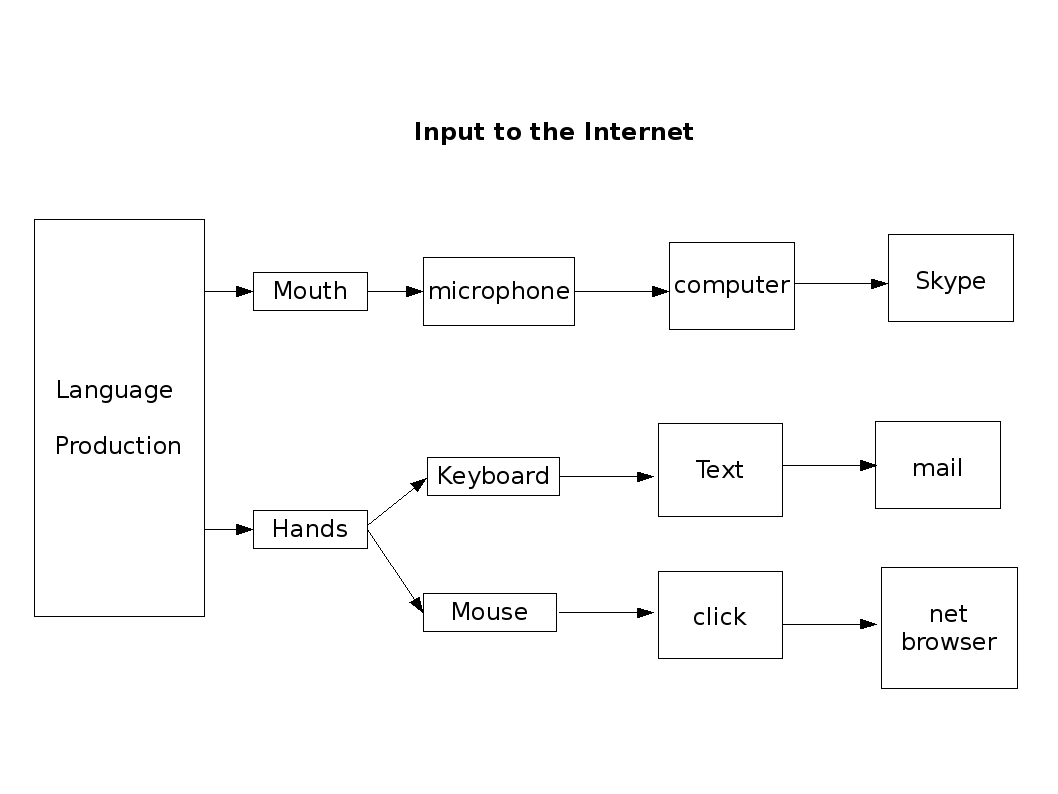

devices can be used, as illustrated in the case of Professor Stephen Hawking

below:

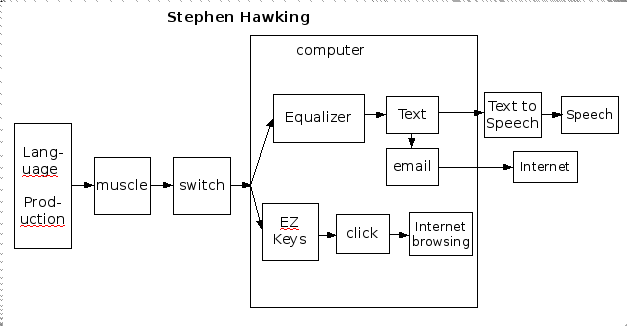

This diagram shows how users typically get information from a computer. Mail, for instance, is displayed on the monitor, which the eyes of the user perceive, and assuming you are able to decode the language, the information you receive becomes knowledge. Alternately, as the lower part of the flow chart shows, software such as Skype produces sound via a sound card and speakers, which the ears of the user convert into signals for the brain. Once again language decoding is involved in coming to know what the person at the other end said. This facility can be used also by persons with visual challenges.

What might prevent you from accessing mail delivered to you via the Internet, assuming you have a connected computer in front of you, could be some problem with your optical system, a "hardware" problem, if you will. Or, you may be unable to understand the language in which the information is composed. This one might consider a "software" problem, that can be addressed by education, while the "hardware" problems typically require technology.

Placing these diagrams one below the other, keeping in mind that one path is blocked for the blind while the other is not, suggests an obvious diversion, which is what the screen reader achieves.

However, the development of a Hindi screen reader was not treated as priority

in the ministries dealing with the problems of the disabled. It took

considerable personal zeal by a few blind technologists to make it happen.

While they themselves were fluent in English too, and might have managed

without a Hindi screen reader, they were moved by the plight of blind Hindi

typists, who amazingly enough, were able to hold their own in the workplace

using manual typewriters, even to correcting errors was nearly impossible for

them. The introduction of computers into the workplace would have been a huge

improvement, had a Hindi screen reader existed. Instead, it cost them their

jobs.

Ever since the early 1990s, when the English screen reader became available in India, the visually challenged community had been urging the government to promote the development of a Hindi screen reader. Since no help was forthcoming, the blind developers began writing the software themselves, giving it the name Safa.

The platform they chose for software development, Visual Basic version 6, was poorly suited to this task, because of its difficulty with Unicode. Its overriding advantage, was that it was then the most accessible software development platform for blind programmers, even when compared to subsequent versions of the same product.

It was only in December 2004 that government funding for the project came through, by which time the lead developer had managed to find a job where he was actually being paid a regular monthly salary.

Confirmation of the revolutionary potential of software such as Safa was quickly forthcoming from the visually challenged community. Students used it in examinations, allowing them to write instead of having to dictate. Writers discovered the joys of speech-enabled word processing. But in the years since the development of the product, it has not created any major ripples.

There are only around 1000 active users, less than 0.1% of those whom it

targetted. No systematic effort has been made to bring it into the education

system as a way of mainstreaming the visually challenged. And nobody seems to

have given thought to the hundreds of millions of illiterate Hindi speakers,

who might use it to inform themselves from the Internet, organize through the

use of e-mail, wikis and blogs, and find myriad other uses.

The screen reader highlights a crucial use to which computers can be put, in

the lives of persons with disabilities: they can not only take advantage of

multiple ways of communicating with a user, but also convert from one medium

to another, and find new ways of ensuring information flow.

Much work still needs to be done on screen readers. Text is only one kind of information. The blind have problems in certain areas of mathematics, such as geometry, where diagrams are used a lot. The conventional approach has been to simply exempt the blind from having to learn maths, as provided for in India's Persons With Disabilities Act, and simply not teach it to them. While this may help the blind pass exams, it closes many professions to them. Hence there is an urgent need to invest serious effort into screen reader development.

However, the screen reader is only one component of a solution, which requires a holistic, rather than a piece-meal approach. The chain is only as strong as its weakest link. The pointlessness of focusing on computers and communication, without addressing language reading and writing skills, as often happens in ICT interventions, is brought out by a diagram such as the one above.

In the case of those with mental challenges, these diagrams may need far

more detail, and the study a broader scope. Given the variety and complexity

of such challenges, we restrict our focus here to those with autism. Problems

faced by those with other kinds of mental challenges are no less severe.

It is really quite appalling, to look at all the different levels at which

persons with autism are discriminated against. Here we are only looking only

at some that impact the ability of persons with autism to access, produce and

disseminate information.

First, very little is known about the condition, if it even deserves to be looked upon as one condition. As an eminent mental health expert points out, "one of the challenges of researching many mental disorders is that the diagnostic criteria are all based on observing behavior, there are no universally accepted 'tests' that are 100% sensitive and specific (well, that is true for most things); and there's a good chance that any group of patients is heterogeneous with regard to their underlying biology; i.e. what we call autism or schizophrenia may be a sort of final common pathway for more than one brain disturbance or pathology... i.e. there may be more than one latent subgroup within our group. So a treatment that might be specific for subgroup A will not work for subgroup B, and in the group as a whole, on the average, we may not see the effect. But since we don't know what the subgroups are, we can't look at them separately." In other words, because we know so little about autism, in effect treat it as a catch-all phrase for many different mental health issues we do not understand, we are unable to find out what works and what does not. Let us compare autism with HIV/Aids. Autism has been known to the medical community for longer, and the numbers afflicted by it are far higher. Yet, compared to HIV/Aids, autism research is in its infancy.

Doctors hold sacred a Latin phrase that means "First, do no harm."

To cite the same expert again, "As an engineer, you can ruin a machine but

not directly cripple or kill another human being; to us, the latter seems

like a more awesome responsibility. If I take someone's autistic child

and offer a treatment that makes the child worse, the parent is not going to

be quite as appreciative of the fact that I was willing to "think outside the

box" and take risks etc. although if the treatment had helped it would have

solidified my reputation as a miracle worker." If you are not sure that the

options available to you are not harmful, it is best to do nothing, which is

what is expected of an ethical doctor in such cases.

Another problem at the research level, is of course that you cannot use

animal trials -- your research specimens are all human. So, if for instance,

vaccines are suspected to overwhelm those with weak immune systems, you

cannot actually deny vaccines to a control group of children to compare. Both

at the research and the clinical level, the medical fraternity seems fairly

helpless.

The most effective way of denying someone information, you might say, would be to not produce it in the first place. Such neglect by the medical establishment is only the beginning, even as far as this fundamental denial of rights is concerned .

The government, confronted with demands from very vocal constituents with

pressing problems, finds it easy to allow to fall between the cracks those

who have a hard time communicating, and therefore are unable to organize.

Autism is not even recognized as a disability by many governments, including

India. In a response dated

8/12/2003 to the Autism Society of India's request for its inclusion in the

Persons With Disabilities Act, the Ministry of Social Welfare and

Empowerment went so far as to say, ”A considered view has been taken that the list of

disabilities considered under the PWD Act 1995 should not be expanded, as

doing so would shift attention and resources away from those whose need is

greatest.”

Right to Information

petitions have also revealed that no ministry keeps track of how many people

with mental challenges are in the school system in the country. The

government even sought to pass a Right to Education bill without paying any

attention whatsoever to the needs of the mentally challenged.

Another excellent means of denial of rights and facilities to those with autism, is to simply not count them. The census makes no effort to disaggregate persons with mental challenges. Also, given that the enumerators are not appropriately trained, and the stigma that attaches to persons with mental challenges, there is gross underreporting.

The facts, when someone does bother to look, are horrifying. According to http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/facts.shtml:

It is surely time to treat the routne abuse of the disabled as a serious human rights issue, that should not be allowed to persist.

The Indian government has ratified this convention, hence its provisions are ostensibly the law in India. This highly significant example of progressive international diplomacy highlights very well the long journey ahead of countries like India, in the manner in which they look after the disabled.

Article 6 of the UNCRPD is devoted to the special problems of disabled women, which indeed are horrific....{to be added}. In response to a Right to Information petition asking how many women with autism there were in India, the government response was simple: it had no information

Similar was the response to Article 7, relating to the rights of children, which requires that "States Parties shall ensure that children with disabilities have the right to express their views freely on all matters affecting them". The government has no idea how many children between 6 and 14 have autism, even though the Right to Education provides for compulsary education for children in that age group. Not having any information relating to the employment of persons with autism, the government isn't bothered by Article 27 of the Convention, which relates to work and employment.

The list goes on, but the point is clear: acts of omission are far more significant in denying rights to persons with disabilites, than acts of commission. Hence the need to look at the problem in a manner that highlights acts of omission suitably.

Influenced by the lack of donor agency and government funding for causes

related to persons with mental challenges, NGOs too have neglected their

problems. There are indeed some NGOs dedicated to autism, but these are

typically run by the mothers of persons with autism. These women have to be

instantly available to their children round the clock. Lacking other sources

of information, and lacking also the luxury of the medical profession of

being able to do nothing, they effectively become researchers. There is

little time left to organize some self-help, let alone to lobby governments

and the medical fraternity. Other than such NGOs started by parents of

persons with autism, almost no NGO in the country devotes significant

attention to this issue.